It takes a certain kind of person to even attempt to do something where the probability of failure is over 99%. Forget what you’ve seen on Discovery Channel about things like BUD/S being only 70-80% failure rates. The reality is that most guys don’t even make it that far. So, by the time you get to something like BUD/S, BRC, or SFAS, you’ve already weeded out most of the applicants. You may or may not be shocked to find out how many guys fail the entry tests.

When someone comes to me stating that they’re going to attempt this journey where the chances of failure far exceed the chances of success, I’m already impressed with them because they have a mindset that you simply don’t see very often these days. They’re average guys with extraordinary determination. I am grateful and thankful to each and every one of them.

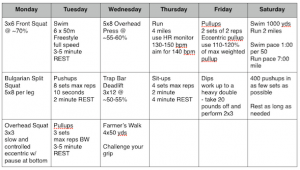

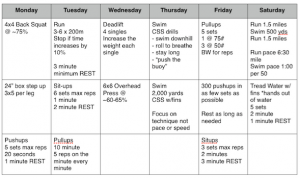

As a coach, I’m not a particularly amazing coach. I didn’t reinvent the wheel, and I don’t do anything all that novel or innovative. What I have found is that simple works best. Everything works. They’re young men, so it really doesn’t take anything magical to make them better. However, I’ve tried just about everything with them. At the end of the day, the most basic and simple things work consistently. These athletes are trying to hold a 6-minute mile pace for 1 to 3 miles. They’re not trying to run a sub 10 second 100m. The training doesn’t have to be complex or periodized to peak on a given day 4 years from now.

I meet people where they are. I don’t have any programs or templates where you just plug numbers in and it spits out a program. I don’t sell them an eBook or an excel spreadsheet. I get everything from D1 athletes, to guys who can’t even do one pull-up. I even had a guy once who told me he wanted to be a Navy SEAL, and he didn’t know how to swim yet. Even if they have previous training background, everyone has different strengths and weaknesses. If I have a guy who ran triathlons, we have to spend more time on strength and bodyweight training, and if I have a guy who played a sport like hockey, we end up putting more focus on endurance.

The strength training is basic and simple, and I don’t have any preference for a particular program. If a guy comes to me saying he’s being doing Starting Strength, I’ll just have him keep doing it rather than making big changes to his current training.

Where the real work lies is in their endurance training. Now, I just want to take a moment to point out that training for selection is not like training for going down range. I have a buddy who is a Master Chief, and his kit weighs around 150 pounds. No one is doing a 4-mile timed run in 150 pounds of kit through the mountains of Afghanistan. Obviously, it pays for him to be strong and to lift heavy. That’s for guys who have already made it through selection.

For guys hoping to go to selection, the first hurdle is passing their PT test. For example, the Navy has the PST which has a 500 yd swim and a 1.5-mile run. If you’re going into the Marine Corps, the PFT has a 3-mile run. Nothing crazy. No one is being asked to run a marathon for their entry level PT test.

This is where I pull from personal experience. When I was training for the Navy, I followed a running program where I just kept adding mileage every week. This turned out to be useless for me. I didn’t get any faster. I just ended up being really good at going very slow for increasingly longer durations. After about 3 months of diligently following this program believing that someday I was going to magically have a breakthrough moment and run faster, I finally decided to change things.

The internet wasn’t as cool back then, I didn’t have Facebook to post on, but there was a forum where people with screen names like Wetwash and Sandfrog would post. I can’t even remember who mentioned the name to me, but some Navy SEAL on a forum told me to look up “Maffetone” and “Mark Allen.” What I found was this formula where you took 180 minus your age, and that was your target heart rate. I figured I’d give it a shot since I couldn’t see any reason why a random, faceless guy on an internet forum claiming to be a Navy SEAL would give me bad advice.

By the time I gave up on the original linear running program I had been doing, I was running 40 miles a week. After a month of doing high days and low days, I already was breaking all my previous numbers and running about 10-15 miles a week. This isn’t to say that my volume didn’t eventually become much higher, but the important part is that I reduced my volume and got faster, much faster.

When guys come to me, they usually have some linear program they printed off some website where they just keeping adding more mileage every week. Maybe that works for some people, but I find that by separating their running workouts into short runs for speed and longer slow pace runs, they avoid overuse injuries and hit their target numbers relatively quickly. If you think about it, it’s really just common sense. If a guy can’t run 400m in 90 seconds, he isn’t going to run a 6-minute mile, and he certainly isn’t going to run 3 miles in under 18 minutes for a perfect 300 score on the USMC’s PFT.

When I work on their top end speed, their run times improve very quickly.

Swimming is the wild card. Just my personal observation, guys who run well tend to struggle with swimming, and guys who struggle with running tend to have an easy time with swimming. It’s probably something to do with physics and their center of gravity, but that really doesn’t change anything in how I help them to prepare. Ideally, they work with me in person. In which case, swimming is much easier because I can just help them to improve their form. I pull from Terry Laughlin. I don’t reinvent wheels, I just use them. Swim downhill and push the buoy. If you watch Stew Smith’s videos, you’ll learn the combat swimmer sidestroke, and once you figure out the proper form for the CSS, swimming gets much easier.

From there, once their technique is solid, it’s not all that different from running. We do short distances for speed, and then really focus on being smooth and steady on longer swims. Kick and glide with an emphasis on learning to glide. I also make a point to really focus on learning to kick off the wall efficiently. This doesn’t matter much for their training later on since guys will be swimming with fins in open water, but you can really take a ton of time off someone’s PST by teaching them how to use the wall, and when a guy clocks in at 8 minutes or less on their 500 yard swim, it also means they have a few extra minutes of rest while the other candidates finish their swim. Don’t underestimate the value of those few extra minutes.

The last element is basic bodyweight PT. My goal is to get everyone to 30 pull-ups and 100 pushups in 2 minutes. Not everyone gets there, but by setting that as the standard, you’d be surprised how close most of them get. We approach it from multiple angles. Some workouts, we just try to get as much volume in as we can, and then increase that over time. Other times, the goal is to get as much work done in the shortest amount of time as we can.

So, just to give an example, I’ll focus on pushups. The various PT tests have time limits for pushups. It’s not enough to do a high number of pushups, the applicant must complete those pushups in a time limit. On the PST for SEAL candidates, they have two minutes to complete their pushups. To address this, I vary the workouts so that they’re developing both capacity and speed. One workout, we might set a goal of 400 pushups total, and that will be done in as few sets as possible, but with no time limit. They can go at any speed as long as they keep moving steadily, and then they can rest as long as they need to between sets. Then to contrast that, in another workout, I’ll have them do something like max reps in 20 seconds, rest for a minute, and then repeat. I try to make sure they’re consistently getting similar numbers of reps each set, so if they get 15 pushups in 20 seconds on their first interval, I want them to stay above 12 reps per interval. When they drop below 12 reps, I’ll have them stop doing intervals because their fatigue is now affecting their speed. Depending on the individual, we might repeat that for six times, and some individuals might be able to do that for ten, or even twenty, sets before their performance starts to decline.

For things like pull-ups or dips, we use different grips, weight vests, eccentrics, oscillatory reps, and other variations. It’s a bit of an art more than a science at times. You see individuals make progress simply by adding volume, but they hit plateaus, and then you have to find a way to break those plateaus. This should be obvious, though it’s often overlooked, but the very first thing I address is their grip strength. If they cannot hang on a bar for two minutes, they’re not going to perform pull-ups for two minutes. We slowly add volume over time, and then things get increasingly harder once they are performing roughly 20 pull-ups. To go from 1 to 10 is relatively easy. To get from 10 to 20 requires some extra work. To get from 20 to 30 is much harder. Just an example of something we will implement to break a plateau would be doing as many reps as possible with a 50-pound weight, immediately dropping to a 25 pound for more reps, then no weight for more reps, and then finishing with a resistance band to give them some assistance to complete more reps. Then we would contrast that workout with a different workout like a supramaximal eccentric weighted pull-up.

That’s just a brief overview of some of the things we do, but the trick is in how you manage the different demands and the overall program. There is so much variation from one individual to the next in their training background that you have to evaluate what they need and what they do not need. You’re basically trying to make them well rounded, and identifying their weaknesses and addressing them is a critical part of the process.

If there was one thing I could pass on to other coaches who work with military, it would be to address their feet. Personal experience again here, I had 12 stress fractures in my metatarsals. Running in boots is definitely not ideal for foot strike mechanics, and so you’re going to have to prepare them for less than ideal situations. I cannot begin to tell you how important it is to address their feet. I have had so many guys come to me with stress fractures and shin splints. I’ve had guys who went to BUD/S or SFAS and didn’t make it because of things like stress fractures. One of the first things I do with everyone is evaluate their feet. I have seen this debated countless time, maybe our shoes provide too much support, but many people have weak feet, and they over-pronate. When we address the foot and strengthen their foot (especially the arch), they stop developing stress fractures, shin splints, knee pain, ITB, and so forth.

The final takeaway is training versus testing. I know that coaches get this, but when you’re working with these individuals who are seeking careers in Special Operations, you have a bunch of sled dogs. They will run themselves to death. 99% of what I do is pulling them back and keeping them from overtraining. I am not a cheerleader. I will not motivate you. I don’t have anyone that I have to push. If I had to push someone, I would tell them that I cannot help them, and they should seek something else.

I comment that I “inherit overtrained athletes.” It’s like any other field, people go to the doctor when they’re sick, people take their car to the mechanic when it’s broken. Guys usually only come to me after they tried to do it on their own and didn’t make the progress they expected. They are highly motivated individuals who will push themselves to their limits without even being asked. That’s why using the heart rate monitor works so well with them. It gives them an objective number to focus on which then holds them back from going all out. I’ve seen guys try to sprint 3 miles. They leave the starting line at full sprint and continue pushing as hard as they can for the entire run. The idea of pacing themselves and saving something doesn’t even cross their mind. Same reason why I use a stop watch for their rest intervals. You must rest the full interval. If I say one minute rests, then we do one minute rests, and I hold the stopwatch up for them to see it. Without it, they would tell me that they’re recovered and ready to go again every 30 seconds. They come to work, and they work hard. I admire that, and I commend them for it, but that’s why I say that most of what I do is pulling them back.

It’s very important that you recognize certain personality types. I have to remind them that not every run, swim, and ruck is a test or time trial. There’s a difference between training and testing. That’s why we practice things like pace, where I’ll have them just hold a 6 minute mile for as long as they can rather than running as fast as they can for a given distance.

It’s worth mentioning that the Navy has done research on personality types of men who successfully complete BUD/S. No surprise, they score very high in conscientiousness on the Big 5 Personality. Just as you would expect, they are driven, self-disciplined, efficient, reliable, and hard working. This is something to keep in mind when coaching them because they tend to be perfectionists and workaholics, which is exactly what they need to be in order to be successful in this endeavor, but at the same time, it’s important to help them learn when to rest.

And that’s why they’re amazing. The old quote, “Hard work beats talent…..” They have work ethic, and while they may or may not have talent, they have a surplus of work ethic. It’s cliche, but you’ve heard it a thousand times because it’s true. I truly love working with them. I don’t have any of the problems you see in sports. Everyone that contacts me wants to be there and wants to work. I just do the best I can to keep things simple and point them in the right direction. If you work with these young men, I hope that my experiences give you some ideas and some insights on how to better serve them.

Chad Cilli is a private strength and conditioning consultant from Pittsburgh, PA. He has worked with Navy SEALs, US Marines, Army Rangers, Army Special Forces, and Air Force Pararescue Jumpers as well as professional athletes in the NFL, NHL, and MLB. A former photovoltaic engineer and exercise physiology student, he applies a systems engineering approach to athletic performance. Feel free to contact Chat by email with any questions here: injewelcoaching@gmail.com

We are hoping to provide the best possible content for strength coaches with each of our shows. If feel this could provide value for anyone else in the strength and conditioning field please feel free to share.

Enjoy the content? Then you should check out The Strength Coach Network!

You can find sensational content just like this in The Strength Coach Network. As a member of The Strength Coach Networks, you can access over 200 hours of the highest-level lecture content just like this one for 48 hours for only $1. Follow the link below to sign up and use the code CVASPS at check out to get a 48 hour trial for only $1. Check out The Strength Coach Network Here! https://strengthcoachnetwork.com/cvasps/

#StrengthCoach, #StrengthAndConditioningCoach, #Podcast, #LearningAtLunch, #TheSeminar, #SportsTraining, #PhysicalPreparation, #TheManual, #SportTraining #SportPerformance, #HumanPerformance, #StrengthTraining, #SpeedTraining, #Training, #Coach, #Performance, #Sport, #HighPerformance, #VBT, #VelocityBasedTraining, #TriphasicTraining, #Plyometrics