Dr. Michael Yessis’ 1×20 progressive training method yields multiple benefits in developing the physical qualities in novice and youth athletes. It exposes the athletes to several resistant exercises in one sitting to strengthen the major joints and provide robustness through the different actions. Doc has noted that the significant benefits of this method include: developing the athlete’s connective tissue quality, strengthening motor unit synchronisation, enhancing aerobic capacity and improving muscular capillarisation. This comes at a much lower cost when doing business to achieve those adaptations. After all, novice athletes don’t need intense stimuli to have positive adaptations, training at high intensity would be surplus to requirements. This would be like a doctor prescribing chemotherapy for a cold as Jay and Yosef have said many times.

Dr. Michael Yessis’ 1×20 progressive training method yields multiple benefits in developing the physical qualities in novice and youth athletes. It exposes the athletes to several resistant exercises in one sitting to strengthen the major joints and provide robustness through the different actions. Doc has noted that the significant benefits of this method include: developing the athlete’s connective tissue quality, strengthening motor unit synchronisation, enhancing aerobic capacity and improving muscular capillarisation. This comes at a much lower cost when doing business to achieve those adaptations. After all, novice athletes don’t need intense stimuli to have positive adaptations, training at high intensity would be surplus to requirements. This would be like a doctor prescribing chemotherapy for a cold as Jay and Yosef have said many times.

I’ve been experimenting with the 1×20 method for over two years now and I’ve built it into my own system for the group of youth athletes that I train. So far it’s been relatively successfully regarding the continuous increase in standing broad jumps (my performance marker), and anecdotally I’ve seen very few non-contact injuries with the athletes during this time. Nevertheless, when I originally first heard Jay discussing the idea of prescribing only a single set for each exercise I thought it was crazy talk! Only 1 set?! But university has taught me that a minimum of 3 sets is a must! And 20 reps will never develop strength, that’s just endurance. Come to think of it, if you can Squat 125kg (275lbs) for 20 reps, you’re pretty dam strong especially for a lot of field based athletes. So I read Doc’s book on the system he conjured up and it makes perfect sense to me that this is a better way to train youth athletes, as it ticks all the boxes.

With every case for designing a strength programme, however, context is everything. There’s a famous seven letter word to describe the make up of each programme: it ‘depends’. For example, this depends on the athletes you are coaching, the environment you are working in, the equipment that’s available, what you’re aiming to achieve, what you’ve already achieved etc. In my environment, I train out of a box size dungeon which is a 7 m by 5 m gym. Somehow it hosts 3 squat racks, 1 cable machine, dumbbell (DB) rack up to 50kg, 3 benches and soft plyo boxes. All in all, it can fit up to 12 athletes training all at once. It’s snug to say the least with a side order of organised chaos when it’s busy.

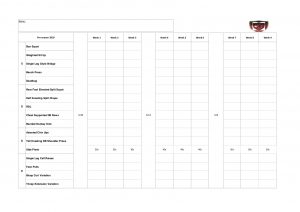

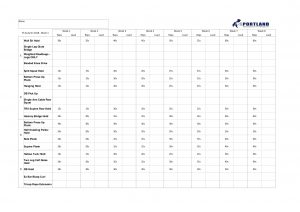

With the constraints of training in such a small space with limited equipment, I break up 20 exercises into 4 sections of 5 with the first 2 sections compromising of more demanding exercises with the final 2 section Rugby Colts 2018 (16-18yrs) This preseason 18-19  involving less demanding single joint, isolated exercises (the fun stuff). I normally split the group in half; in any order, one half will perform the exercises in section 1 whilst the other half completes the exercises in section 2 (whatever equipment / space is available to use). When both groups have finished their respective sections, they swap over. Once the first 2 sections are completed, the guys have the freedom of completing the rest of the programme sheet from sections 3 and 4. Each week I will switch which boys start in which of the first two sections. Combined with the autonomy of not following a specific exercise order within the sections, I think this is a great way to present a new stimulus to the body each session. One week, the boys could begin on goblet squats, the next week they can start on DB pick up or related exercise. Nothing ever seems to stop the battle to be first on the bench press though.

involving less demanding single joint, isolated exercises (the fun stuff). I normally split the group in half; in any order, one half will perform the exercises in section 1 whilst the other half completes the exercises in section 2 (whatever equipment / space is available to use). When both groups have finished their respective sections, they swap over. Once the first 2 sections are completed, the guys have the freedom of completing the rest of the programme sheet from sections 3 and 4. Each week I will switch which boys start in which of the first two sections. Combined with the autonomy of not following a specific exercise order within the sections, I think this is a great way to present a new stimulus to the body each session. One week, the boys could begin on goblet squats, the next week they can start on DB pick up or related exercise. Nothing ever seems to stop the battle to be first on the bench press though.

Another subtle change that can deliver a new stimulus for the body is to progress the difficulty of the exercises before lowering the rep scheme. A simple example of this is to swap the split squat to a front foot elevated split squat then onto a rear foot elevated split squat in the up and coming blocks for the same rep scheme. Youth athletes should be exposed to a large variety of exercises to develop that initial base layer of strength and keep challenging their motor cortex. This method fits perfectly by providing a vast number of exercises that the athlete will undertake in the course of early years of training. However, you can also recycle these exercises by altering the way the resistance is applied to this movement either by getting the athletes to perform them using their bodyweight, holding a DB in a goblet style or in both hands then placing a barbell on their front / back. An idea I’ll be looking to include in the future for athletes that have undergone a few cycles of the system is to add in contralateral exercises. The aim is to connect the lower and upper body in one movement and train the bodies sling systems.

As the overall programme has evolved, I’ve now begun to incorporate longer isometric exercises with the 1×20 model for the beginning athlete. I’ve stolen this idea from Jay as the boys need to own certain positions. This would be of great benefit if the athlete happens to be going through a growth spurt period to cement movement pathways and develop tendon strength for those that suffer from the common tendon growth complainants. I’m currently using a 2:1 ratio of isometric exercises to dynamic which will then continue onto a 1:2 ratio with the introduction of more dynamic actions.

As the overall programme has evolved, I’ve now begun to incorporate longer isometric exercises with the 1×20 model for the beginning athlete. I’ve stolen this idea from Jay as the boys need to own certain positions. This would be of great benefit if the athlete happens to be going through a growth spurt period to cement movement pathways and develop tendon strength for those that suffer from the common tendon growth complainants. I’m currently using a 2:1 ratio of isometric exercises to dynamic which will then continue onto a 1:2 ratio with the introduction of more dynamic actions.

Yet, when finally progressing on to the 14 / 8 rep scheme, after rotating through the programme a few times, you can look into using a triphasic type approach. My overall end goal is to progress the athletes onto a multi set triphasic system, the likes of which have been popularised by Cal Dietz which I use with my senior rugby team. This will be a great opportunity to start teaching and drip feeding the triphasic method into their training. I believe that an eccentric focus for younger athletes will allow them to concentrate on the execution of the particular exercise rather than on how much weight they’re lifting. Regarding the isometric focus, this is a continuation of the longer isometric previously developed. To put this into a bit more context, you have the option of mixing in eccentric, isometric and concentric exercises together in one block or have separate blocks with a progressive emphasis on the eccentric, isometric and concentric phase of each lifts.

A few more variations of how I’ve taken the concept of this method and used it in practice is how I’ve used it with my older senior rugby players. As an aerobic type ‘low’ training day, I use just an upper body + core session (non-barbell lifts) for the boys so they can get a bit of a pump on and strengthen muscles through movement patterns that they won’t commonly perform in the gym on their own. The thinking behind this is to prevent the intensity from being too high on what is meant to be a recovery day. In addition to this, in the past for my younger groups, I’ve made 2 programmes for the day (full body or just uppers + low threshold exercises) and will decide which one to run depending on how the athlete presents themselves in terms of readiness when they enter the gym.

Moreover, the vision in the future for my 1×20 programme is to be in a position to be able to give the athlete autonomy in exercise selection. The movement outcomes will still be given but it’s up to them what exercise they want to do or feel like doing. However, for this to happen, it’s important for me as a coach to educate the athletes on which exercise will fall under each category and the purpose for each movement. It’s the next step in the long term development process and an opportunity of giving the athletes greater ownership and better enjoyment of their training.

Still, I’m sure that there are many coaches out there utilising other variations or similar to which I’m implementing the 1×20 programme. I’m always on the lookout for ways to improve my practice and small additions to generate more productive outcomes. It’ll be great to hear other coach’s views and to begin a discussion on the results they have seen with their athletes.

Who is Marc Stevenson?

Who is Marc Stevenson?

Marc has earned a bachelor’s degree in Strength and conditioning from St. Mary’s University, Twickenham, London in 2015. Since graduating university, he’s been the strength and conditioning coach at Amersham and Chiltern rugby club (Level 6) working with both the senior and academy players. Marc is also the assistant S&C coach for Sportland training & fitness where they have multiple ongoing projects training youth groups and high calibre individual athletes.

We are hoping to provide the best possible content for strength coaches with each of our shows. If feel this could provide value for anyone else in the strength and conditioning field please feel free to share.

Enjoy the content? Then you should check out The Strength Coach Network!

You can find sensational content just like this in The Strength Coach Network. As a member of The Strength Coach Networks, you can access over 200 hours of the highest-level lecture content just like this one for 48 hours for only $1. Follow the link below to sign up and use the code CVASPS at check out to get a 48 hour trial for only $1. Check out The Strength Coach Network Here! https://strengthcoachnetwork.com/cvasps/

#StrengthCoach, #StrengthAndConditioningCoach, #Podcast, #LearningAtLunch, #TheSeminar, #SportsTraining, #PhysicalPreparation, #TheManual, #SportTraining #SportPerformance, #HumanPerformance, #StrengthTraining, #SpeedTraining, #Training, #Coach, #Performance, #Sport, #HighPerformance, #VBT, #VelocityBasedTraining, #TriphasicTraining, #Plyometrics